Current Projects

There are several active projects going on at a single time at WVACS. The easiest way to become involved in any of these projects is to attend one of our Project Weekends and get to know us! The majority of WVACS projects are involved with survey, that is mapping the cave. Surveying involves someone making stations, two people reading instruments that give azimuth and inclination from point A to point B, and a sketcher to draw the cave passage detail. But surveying is not what all WVACSers do, there are always other projects going on such as surface digging.

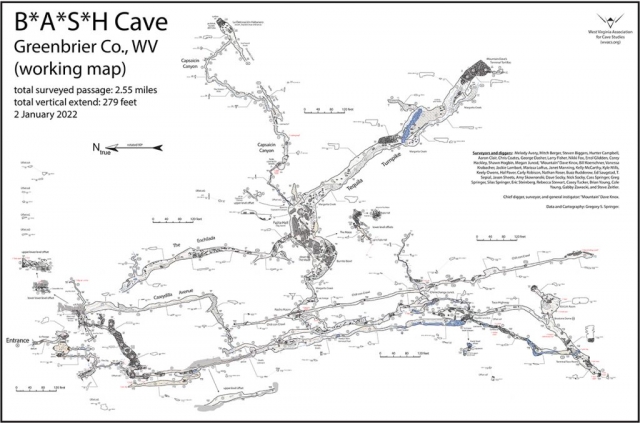

B*A*S*H Cave

Bash Cave is located on the western side of Greenbrier County at the southern end of a large blind valley. The entrance is at the base of an impressive high wall where a seasonal stream flows into it. This cave is formed in the Hillsdale Limestone.

The original name of this cave was Balfour’s Aerial Suck Hole, and is called BASH for short. A dig in 2018 has broken into a significant amount of passage, extending the cave’s length to over two miles. Most of the cave’s passages are tight crawls in wet-ish conditions. However, has been a large room and large river passage discovered deep within the cave. There are still a few leads left, one of them being a breakout in December 2021 — the cave never seems to end! Visiting this wet cave in the winter time is proven to be brutal as the cave sucks in the cold air.

Fajita Hall - Photo by Nikki Fox

Head wall at the entrance.

Ancient animal claw markings.

The tight entrance series.

Margarita Creek - Photo by Nikki Fox

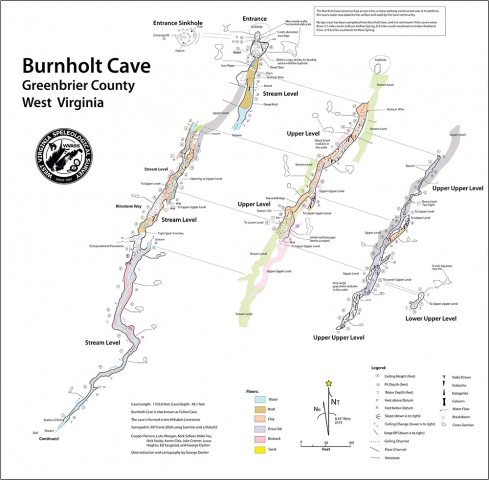

Burnholt Cave

Burnholt Cave, also historically called Fullen Cave, was once used as a domestic water supply. In the cave, a concrete dam was constructed to make a reservoir for the collection of water. Also during this time, an archway over the sinkhole was built and has since collapsed. The only evidence of the concrete creation above the cave are some of its foundation blocks.

Burnholt is formed in the Sinks Grove Limestone. This cave is gated and managed by the West Virginia Cave Conservancy. There are multiple levels of passages in the cave — the lower passage contains the stream and the upper levels are generally highly decorated with squeezes, crawls, steep exposed climbs, canyons and small dead-end pits. Its water has been dye traced to Davis Spring.

Canyon Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Checking out a pit

Formation Gallery - Photo by Nikki Fox

The gated entrance

A Cave Cricket

Stalactites

Entrance Room - Photo by Nikki Fox

Stream Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Dry Cave

Located in eastern Greenbrier County, it is a unique gem among the thousand other known caves in Greenbrier County. Formed in the Tonollaway Limestone, Dry Cave is anything BUT a “dry” cave. The cave gets its length from the multi-level passage development along a very steep bedding plane in which the cave is formed.

The first generation surveyed several miles of passages in the late 1960s and early 1970s before they moved on to even bigger caves elsewhere. A second generation resurveyed the original discoveries and added some new footage in the 1980s making the cave 3.2 miles.

Enticed by the many leads known in Dry, a third generation began a resurvey in 2011. WVACS surveyed four miles between 2011 and 2017, discovered multiple significant upper levels, and a way around the “end” of the cave — two miles from the entrance — called The Bitter End. The Better End, which was discovered in 2019, is still going strong and the cave is currently at 8.76 miles. There was 1.728 miles surveyed in 2021, a new record for the most footage mapped in Dry Cave during a year!

PLEASE NOTE: Dry Cave is CLOSED and only open to WVACS Project Trips.

Cave Bacon - Photo by Nikki Fox

Snake Dancers- Photo by Nikki Fox

Upper Level - Photo by Nick Socky

Unique Square Sodastraws- Photo by Nikki Fox

Formation Gallery Reflected in Water- Photo by Nikki Fox

Large Helictites - Photo by Nikki Fox

Animal Bones- Photo by Nikki Fox

Cave Pearls - Photo by Nick Socky

Sodastraw Gallery - Photo by Nick Socky

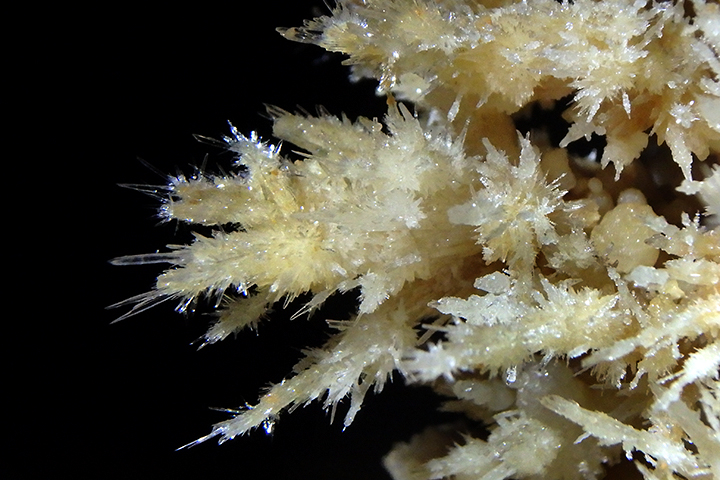

Aragonite Bushes - Photo by Nikki Fox

Aragonite Bushes - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Better End - Photo by Nick Socky

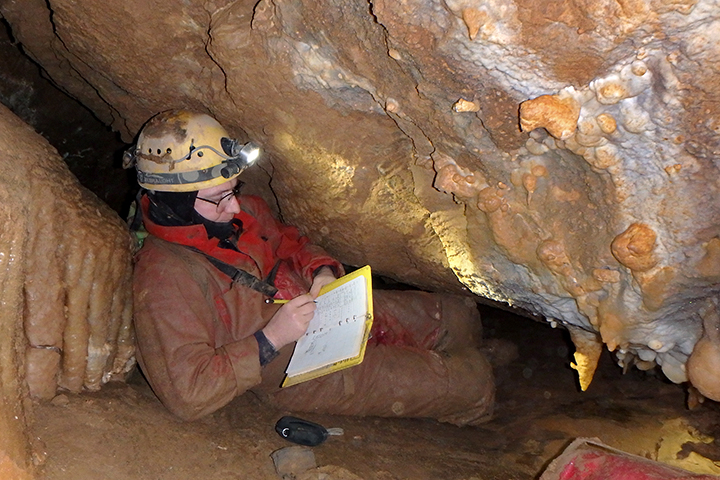

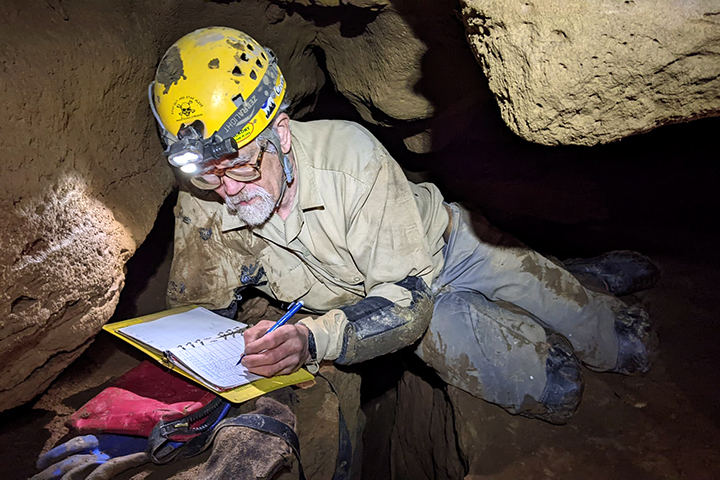

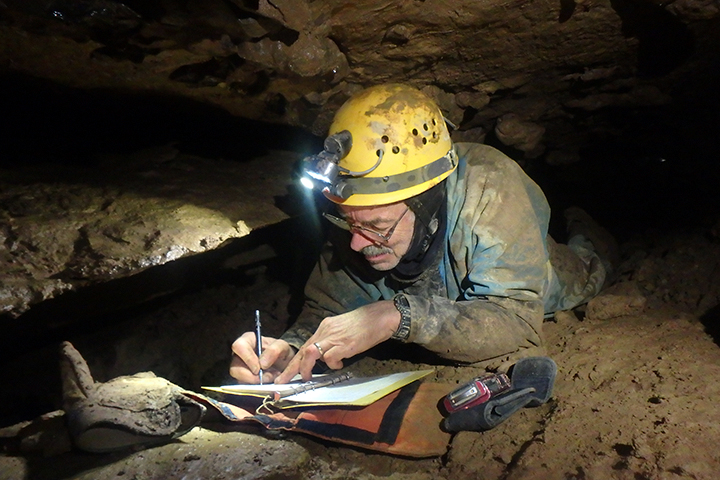

Reading Instruments - Photo by Nikki Fox

Discovery of The Better End- Photo by Nikki Fox

Sketching Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Rock Fold - Photo by Dave Socky

Abundant Formations- Photo by Nikki Fox

A bypass crawl - Photo by Nikki Fox

Flowstone & Formations - Photo by Nick Socky

Air in The Blowhole- Photo by Nikki Fox

Dry Cave Entrance - Photo by Nick Socky

Friars Hole Cave System

The Friars Hole Cave System is the largest cave in West Virginia. Since 2014 a crew of has been pushing leads. As of January 2022, the cave is currently at 50.11 miles long — making West Virginia’s FIRST 50-mile cave system! The cave itself straddles the Greenbrier and Pocahontas County line, with five entrances in each county. Friars is composed of a system of strike-oriented main drains in the upper Greenbrier Limestone that has developed on three distinct levels. The levels are interconnected to each other, and to the surface, by a web of infeeders, pits, canyons, thrust faults, and floodwater mazes. Where the cave is along steadily dipping limestone, it produces beautiful trunk passages. Where the cave hits faulting and insoluble rock layers, it produces breakdown and sumps.

Friars has a rich history of exploration, complex landowner relations, and people becoming addicted to the system, including Lew Bicking who took interest in the cave when he visited the Crookshank Entrance in November 1962. The main push in mapping Friars was in the 1970s — a decade of connecting most of the area caves into the the system. Current exploration, with much of it comprising of bolt climbs and digs, is ongoing in this intricate system. Many have heard the Friars Hole namesakes: Monster Cavern (one of the largest underground rooms in West Virginia), Rubber Chicken Highway, Canadian Hole, Snedegars, Crookshank, Toothpick, and Dung-Ho Way. The cave awaits more discoveries.

Anastomoses Crawl - Photo by Nikki Fox

Snedegars Canyon - Kevin Downey

Going Through a Sump

Layered Calcite Formations

Surveying Passage

R.I.P. Lew

Small Waterfall

The Crow's Nest - Photo by Nikki Fox

Monster Cavern - Ryan Maurer

Caver-to-Caver Warning

Hypothermia Shelter

Rubber Chicken Highway - Ryan Maurer.

Gypsum Curls

Southern River Borehole - Photo by Nikki Fox

Crookshank Entrance

Snedegars Wall Fill - Photo by Nikki Fox

Snedegars Entrance Bore - Kevin Downey

Monster Cavern - Photo by Nikki Fox

Decorated High Passage

South Entrance - Ryan Maurer

Allegheny Wood-Rat Sketleton

Fossil

Large Room in Snedegar's - Photo by Nikki Fox

Snedegars Trunk Passage - Kevin Downey

Stream Crawl

Druid Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Snedegars - Ryan Maurer

Dry Southern Borehole - Photo by Nikki Fox

Solution Tube - Photo by Nikki Fox

Crawdad On Rope

Snedegars Borehole - Kevin Downey

Higginbotham Cave System

The Higginbotham caves are actually two large cave systems (No. 1 and No. 4) and several smaller caves, all of which are formed in the Union Limestone. The entire system is currently listed at 2.83 miles. The caves are located near the northern boundary of the Davis Spring Basin — the largest karst basin in West Virginia at 73 square miles.

The caves are not sequentially numbered and the main stream flows from No. 1 to No. 4. Water from the other caves flow into either No.1 or No.4. There are multiple entrances to No. 1 and due to a hillside collapse one cannot travel directly between No.1 to No.4. However, there is a surface entrance where the water from No.1 siphons to No. 4 near that cave’s surface entrance. Resurvey of the entire system was started in 2018.

Higginbotham #1 Entrance - Photo by Dave Riggs

Higginbotham #1 Entrance - Photo by Dave Riggs

Sediment Layers - Photo by Dave Riggs

Coral Fossils - Photo by Dave Riggs

Ceiling Anastomoses - Photo by Dave Riggs

Cave System Entrance - Photo by Dave Riggs

Stream Cascade - Photo by Ed McCarthy

Stream Crawl - Photo by Dave Riggs

Water Passage - Photo by Dave Riggs

Higginbotham #1 Entrance - Photo by Wayne Perkins

Formations - Photo by Dave Riggs

Round Room - Photo by Dave Riggs

River Boarhole - Photo by Dave Riggs

Formation Gallery - Photo by Ed McCarthy

Water Chute - Photo by Ed McCarthy

Higginbotham Formations - Photo by Ed McCarthy

Stream Passage - Photo by Dave Riggs

Great Savannah Cave System:

The Great Savannah Cave System (GSCS) was created when historic Maxwelton Sink Cave and historic McClung Cave was connected on Aug. 31, 2019. The sump separating upstream Sweetwater River in Maxwelton Sink Cave and downstream Freeman Avenue in McClung Cave was dove from the downstream historic McClung Cave side. The dive was successful, and the passage surveyed, thus creating the GSCS.

In February 2022, the cave was pushed past the 50-MILE MARK, making the SECOND 50-mile cave in West Virginia! As of March 2022 the system is now at 50.26 miles, making it the 6th longest cave system in the United States.

Historic Maxwelton Sink Cave

The main Cove Creek entrance was originally dug open in the 1960s by various groups of cavers. It was the only means of access until the second entrance, the Airport Entrance, was found. In 1969, a hurricane sealed shut the Cove Creek entrance and around the same time the Airport Entrance was sealed shut with the building of a parking lot at the Greenbrier Valley Airport. The cave was completely sealed shut from visitation for nearly 40 years until the Scott Entrance was dug open in late 2003. This entrance is now gated and owned by the West Virginia Cave Conservancy.

The first map of Maxwelton Sink Cave was produced in 1971 and was 10 miles in length. With the new Scott Entrance, WVACS mounted the resurvey efforts and as of January 2022, 14.86 miles has been currently surveyed. There are many leads left and in the past couple years there have been breakouts in areas like the Thunder Dome complex, Classic Canyon, and Consent Canyon.

Cascade Causeway - Photo by Nikki Fox

Heaven Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Waterfall Drop - Photo by Nikki Fox

Heaven Formations - Photo by Nikki Fox

Spaghetti Junction - Photo by Nikki Fox

Muddy Footprints

Large Aragonite Bushes - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Coliseum - Photo by Nikki Fox

Water Droplet - Photo by Nikki Fox

Thunder Dome - Photo by Nikki Fox

Crystals

Heaven Drop - Photo by Nikki Fox

White Ghost Formation - Photo by Nikki Fox

Giant Helictites - Photo by Nikki Fox

Highway to Thunder Dome - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cove Creek - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cascade Causeway - Photo by Nikki Fox

Sweetwater River Extension

The Sweetwater River Extension from historic Maxwelton Sink Cave was discovered in 2016. The mud dig, which was later named The Fox Hole after the caver who mounted, organized and tackled the first exploration since, marks the beginning point of new passages comprising the Sweetwater River extension. Sweetwater is estimated to be the main trunk passage on the eastern side of the Davis Spring Drainage Basin, the second-largest karst basin in West Virginia that encompasses more than 73-square miles. Davis Spring, the main resurgence, is the largest spring in West Virginia.

Sweetwater has proven to be a season-dependent cave; meaning that entry is only safe during low-water conditions. Precipitation is a real threat when going into the far reaches of Sweetwater. Back flooding at multiple locations throughout the southern part of the system is a serious danger, potentially trapping cavers and drowning them.

As of January 2022 a total of 12.23 miles of passage has been surveyed in Sweetwater. There are many leads yet to be pushed by a small crew of dedicated cavers in this “death trap.”

NordicTrack Explorers - Photo by Nikki Fox

Sweetwater River - Photo by Nick Socky

Cloud City - Photo by Nick Socky

Downstream Sweetwater - Photo by Eric Landgraf

Upstream Sweetwater River Sump - Photo by Dave Socky

Bolt Climb - Photo by Dave Socky

Surface Salamander - Photo by Nikki Fox

Surveying Wet Walnuts Way - Photo by Nikki Fox

Dog-Toothed Spar - Photo by Nikki Fox

Upstream Covert Creek - Photo by Dave Socky

Upstream Sweetwater River - Photo by Nikki Fox

Pleistocene-era Horse Tooth - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cloud City Spar Lilly Pads - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Nest - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Fox Hole - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Fox Hole - Photo by Nikki Fox

Covert Creek - Photo by Nikki Fox

Coral Fossils - Photo by Nikki Fox

Echo River - Photo by Nikki Fox

Echo River Mud Bank - Photo by Nikki Fox

Surveying Wet Walnuts Way - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cousin It Pit - Photo by Carl Amundson

Terminal Sump, Downstream Sweetwater River - Photo by Nikki Fox

Covert Creek Waterfall - Photo by Nikki Fox

High Hopes' Cloud Canyon - Photo by Nick Socky

Gypsum Flowers - Photo by Dave Socky

Drilling - Photo by Nikki Fox

Bolt Climbing the Great Escape - Photo by Nikki Fox

Covert Creek Infeeder - Photo by Dave Socky

The Retreat Ceiling - Photo by Eric Landgraf

Echo River Upstream Sump - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Pato Mojato - Photo by Nikki Fox

Ghost Camp - Photo by Nikki Fox

Sweetwater River - Photo by Nikki Fox

Ghost Camp Shenanigans - Photo by Nikki Fox

Bittersweet Falls - Photo by Nikki Fox

High Hopes Formations - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cove Creek Feeding into Sweetwater River - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Fox Hole - Photo by Nick Socky

CrawlMaster 900 - Photo by Nick Socky

Foxtails in Cloud Canyon - Photo by Carl Amundson

The Didgeridoo - Photo by Nikki Fox

Historic McClung Cave

McClung Cave’s only open entrance is the WVCC-owned Lightener Entrance. It is vertical — with an entrance climb down to a 45-foot pit followed by another 21-foot pit into a decorated room where the passage eventually connects into the Tufa Trail section of historic McClung.

A detailed map was produced by Joseph Caldwell using survey notes from the 1950s to 1990s and was estimated to be 18 miles long. Since McClung is now part of the GSCS, an effort by WVACS to remap the cave has been mounted. Since the first resurvey in 2019, there has been over 4 miles of new passages added to the cave. Survey is ongoing and there is much still left in the cave to tackle. As of January 2022, the cave is 22.33 miles.

The Glacier Room - Photo by Nikki Fox

Small Passage - Photo by Nick Socky

McClung Freeman Ave - Photo by Ed McCarthy

Flowstone Wall - Photo by Nikki Fox

Thrust Fault - Photo by Nikki Fox

Formation Alcove - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Connection Dive - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Connection Dive - Photo by Nikki Fox

McClung Historic Entrance - Photo by Nikki Fox

McClung American Spirit Room - Photo by Nikki Fox

They Gymnasium - Photo by Nikki Fox

Broomstick Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Broomstick Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Top of Third Drop - Photo by Nikki Fox

McClung Caynon - Photo by Kevin Downey

The Tufa Trail - Photo by Nikki Fox

McClung Tight Passage - Photo by Dave Socky

McClung Sketcher - Photo by Dave Socky

The Second Drop - Photo by Nikki Fox

McClung Seven Fingers - Photo by Dave Socky

McClung WVACS Room - Photo by Dave Socky

Mapping Passages - Photo by Nikki Fox

Water Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Surveying the Dive Connection - Photo by Nikki Fox

Tombstone - Photo by Nikki Fox

Reynolds Cave

This Pickaway Limestone cave was originally surveyed in the 1960s and a bare-bones map was produced. The cave passage mostly comprised of tight canyons developed in a slick, greasy shale layer and is rather treacherous. The only room of any size the entrance room. There is potential for this cave to connect to The Hole System, a contact cave to the north consisting of over 20 miles of passages.

Cave Cricket - Photo by Nikki Fox

Digging Entrance Open

The Entrance Room - Photo by Nikki Fox

Delicate Gypsum Formation - Photo by Nikki Fox

Tight Canyon Passage

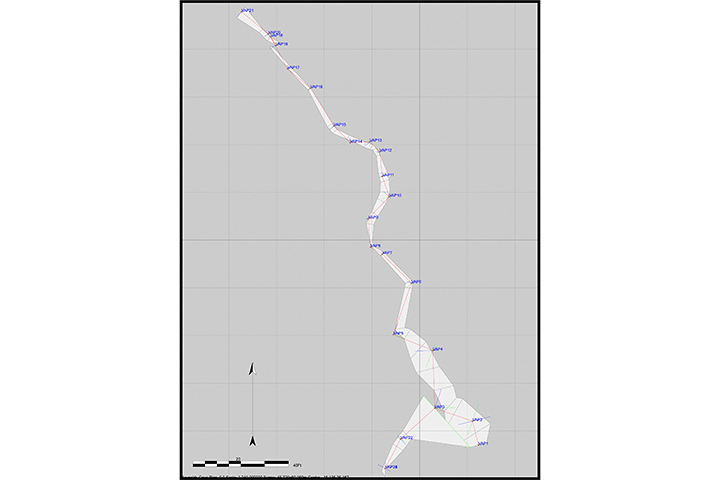

Working Map

Sinks of the Run

The cave entrance is at the base of a large blind valley where a stream cascades into an opening 11 feet tall and 20 feet wide. This cave is very prone to flooding, as all of the water in the valley drains into the cave. Developed in the Union Limestone, there are multiple pits and vertical drops in this cave, the longest being at 106 feet.

It was discovered and named by Bill Jones. The first survey first in the cave was in November 1968. The team mapped 1,112 feet that day and were forced to stop since they encountered the first pit. Since then, there was a resurvey of the cave from 1980-81 and a map was produced. This cave has had multiple landowners through the years, both granting and denying access. In early 2020, a third generation of cavers have started yet another resurvey of the cave. New passages have been found and exploration is ongoing. The number of rigged pitches/pits has increased from 5 to 11. There are currently three domes to climb and 11 going leads. As of November 2020, the cave’s length is 7,750 feet (1.47 miles) and depth is roughly 300 feet.

PLEASE NOTE: Sinks of the Run is CLOSED from May until November and is only open for WVACS project trips.

The Second Pit - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Remembering Well - Photo by Ryan Maurer

Ascending Second Pit - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Ascending Second Pit - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Top of Perseus Pit - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Remembering Well, Pit 4 - Photo by Ryan Maurer

Lower Level - Photo by Nikki Fox

Perseus Pit Top - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Probe Installation - Photo by Ryan Maurer

Perseus Pit Bottom - Photo by Elliot Stahl

Climbing Second Pit - Photo by Brian Masney

Perseus Pit - Photo by Ryan Maurer

Lower Level - Photo by Dave Riggs

Between Pits - Photo by Brian Masney

Windy Mouth Cave

The Windy Mouth resurvey project was started in April 2015. From Jim Hixson’s original survey, the cave was estimated to be 18 miles long. Over the past 5.5 years, 17 miles of passage has been mapped with over a mile of new cave discovered from doing aid climbs. Many more leads still remain and the project should be reaching the fabled 18 miles in 2021. The main survey phase of the cave is complete and it has transitioned into the mop-up phase. Even though the returns are diminishing, there is still new passage and exciting things being found in the cave.

Formed mostly in the Hillsdale Limestone, only one entrance to the cave is currently known. Apart from the infamous entrance crawl, Windy Mouth offers a wide variety of passage ranging from paleo walking passage, joint controlled canyons, large breakdown trunk passage, waterfalls and stream passages, and many, many crawls. Most of the cave is horizontal but there are a few ropes in the cave. Windy Mouth is also quite decorated with formations galleries, wind-swept helictites, gypsum formations, and aragonite bushes. It is recommended to bring knee pads if you decide to experience the glory of Windy Mouth. In January 2021, the survey passed the 17-mile mark. As of December 2021 the cave broke the 18-mile mark with the new length now at 18.06 miles! Crawl on!

Manganese-covered Mud - Photo by Nikki Fox

Waterfall Room Thrust Fault - Photo by Nikki Fox

Pistachio Room - Photo by Nikki Fox

Caver in a crawl - Photo by Nick Socky

Gypsum Flower - Photo by Nick Socky

Supe Buge - Photo by Paul Winter

Bobcat Tracks - Photo by Nikki Fox

Helictites - Photo by Nick Socky

Gypsum Flower - Photo by Nick Socky

Spar-lined Pool - Photo by Nikki Fox

Fossils - Photo by Nikki Fox

Wasted Youth Passage - Photo by Nick Socky

The Nasty Crawls- Photo by Nick Socky

Crawling - Photo by Nikki Fox

Maccrady Shale Layers in Second Canyon - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cave Camp - Photo by Nick Socky

Mapping a Small Passage - Photo by Nikki Fox

Entrance Series - Photo by Nick Socky

Lower Levels - Photo by Nikki Fox

The Milky Way - Photo by Nick Socky

Surveying - Photo by Nick Socky

Tight Canyon - Photo by Nick Socky

Upstream Second Canyon - Photo by Nikki Fox

Gypsum & Aragonite - Photo by Nick Socky

Canyon Passage - Photo by Nick Socky

Upper Level - Photo by Nikki Fox

Lower Level Stream - Photo by Nikki Fox

Lower Level Flowstone - Photo by Nick Socky

Hiking to the Cave - Photo by Nikki Fox

The View - Photo by Nick Socky

Gypsum Flower - Photo by Nikki Fox

YUGE Dome - Photo by Nick Socky

Bolt Climbing - Photo by Nikki Fox

Cavers at L - Photo by Dave Socky

Shattered Ladder Climb - Photo by Nick Socky

Surveying a Crawl - Photo by Nikki Fox

Formations - Photo by Nick Socky

Iron-stained Sodastraws - Photo by Nick Socky

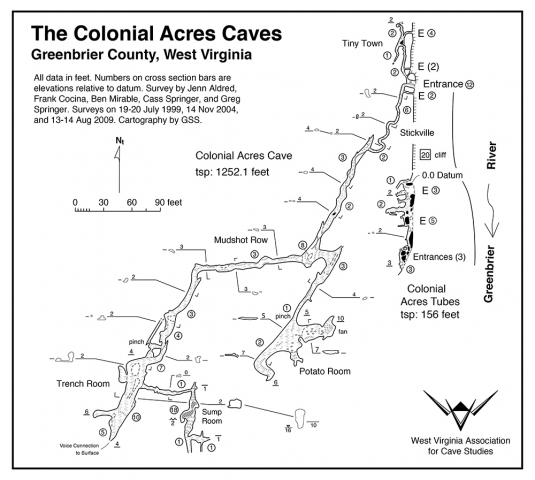

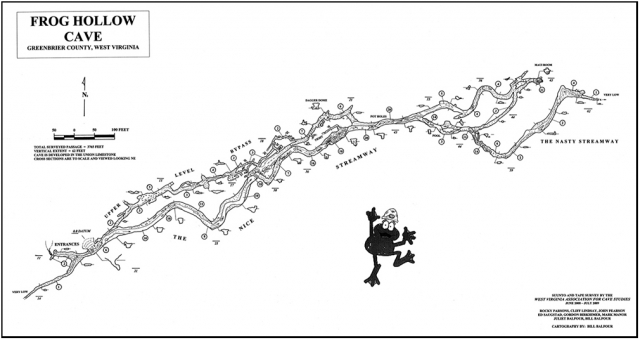

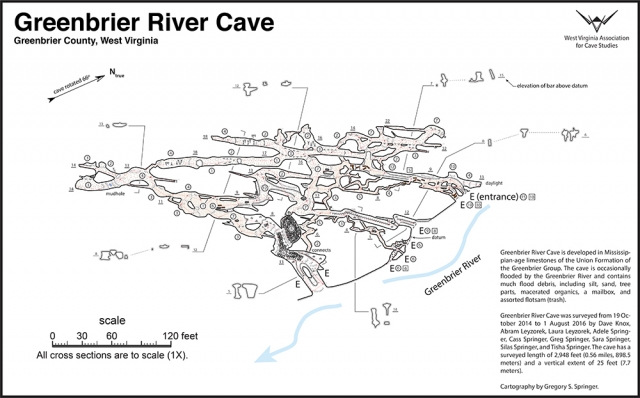

Completed Recent Projects

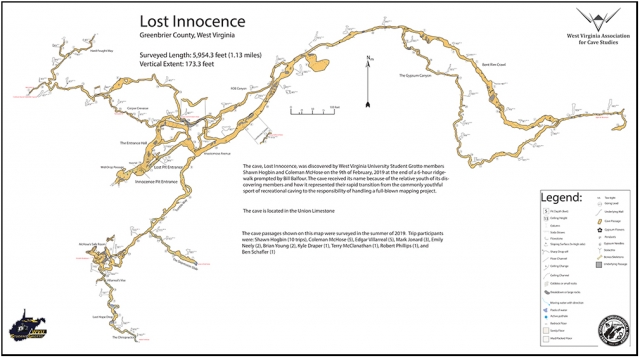

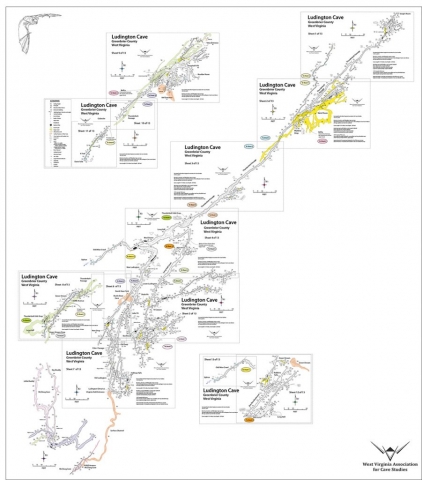

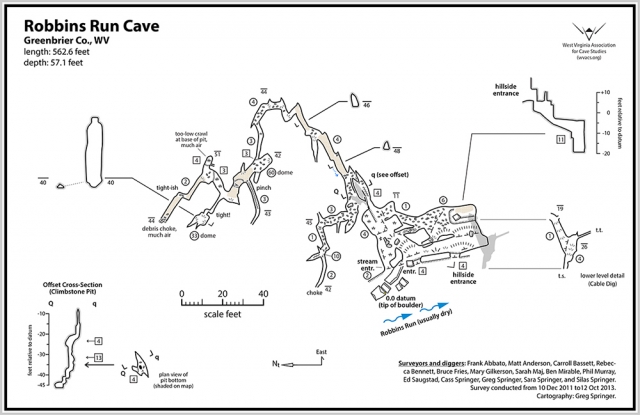

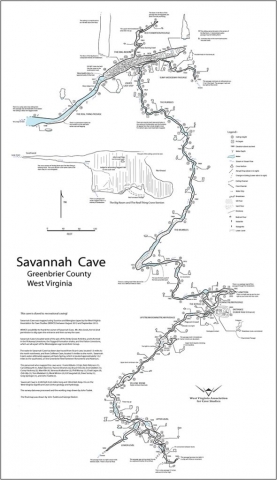

The following are recent maps surveyed, drawn, and produced by WVACS members.